Some time ago, our youngest daughter stopped to ask us whether our parents had allowed us to download apps to our iPads without permission when we were children. She was horrified when we explained to her that iPads weren’t even a thing back then. This then led to a long discussion where my husband and I started to list all of the things that weren’t invented 40-50 years prior or, as our youngest daughter suggested, “in the olden days”. The list was quite large: video cassette recorders, DVD players, CD players, the internet as we know it, the windows operating system, computers as we know them, digital cameras, mobile phones, and so forth.

Reflecting on this later, it occurred to me that there has, in my opinion, been some massive technological change during the past 40-50 years. I remember as a young child not even 50 years ago that we didn’t have a phone in our house. Plus, there were still telephone switchboards in some towns in Australia at that time. Today, every house seems to have at least one incredibly fancy smart phone in the house, if not more. We were grateful for our black and white TV that my Dad made from old parts; today families have multiple slimline, flat screen TVs spread throughout their house. This, I think, is all significant change, which occurred in a relatively short period of time.

In addition to the technological changes, society has been changing in many different ways. Our beliefs and values are changing. What was once considered unacceptable may now be considered acceptable. An example of this is society’s shifted view of marriage as an institution. When I was growing up, there was a very strongly held view within western society that marriage was strictly between a man and a woman and that a couple “had” to be married if they were going to live together or have children. Now, we tend to accept that people have children when they want to, regardless of whether they are married. We’ve also seen shifts in marriage laws, with the introduction of same sex marriage in many countries. Our truths are changing.

As we look even more closely at ourselves in our everyday lives, we see constant change. People seem more busy these days. There appear to be more pressures on us to achieve in work, in life, as a member of a family, as an individual or whatever the case may be. Often it seems that we are committed beyond capacity as we struggle to maintain ourselves in a constantly changing world.

When everything around us is constantly shifting, we can become caught up in old ways of being and doing. These ways of being are often what we have learned from a very young age; they are what we know. They are ways of being that have often served us very well. And then, with the change that is happening around us, one day these ways of being don’t serve us any more. Often, we don’t even realise. We continue to operate from old ways of being that are no longer useful and, eventually, we can start to feel as though we are suffering when these ways of being don’t provide us with the results we are after.

My interpretation is that being trapped in old ways of being can happen to individuals, to groups, and even to societies.

I recently saw what I think was an example of society being trapped in old ways of being when I saw an online news article about a cricketer who supposedly “came out” on social media. (As it turned out, the cricketer had posted a photo of himself, his mother and and a male friend, celebrating a birthday. A misunderstanding resulted from his post, and the media declared it as the cricketer “coming out”, only to be told by the cricketer later that the male in the photo was a friend, and the cricketer wasn’t gay. It is the reaction of the media to a supposedly homosexual relationship that piqued my curiosity for this reflection). When the photo was originally interpreted as a “coming out”, the cricketer received much support by the Australian public. I loved that he was receiving support, and I also experienced a mix of feelings. I was in awe of the amazing courage that “coming out” would no doubt take. I cannot even imagine what this must feel like. However, I was also sad that declaring love for someone of the same gender could still be seen as such a big thing. I reflected on this for some time.

The last state in Australia to decriminalise homosexuality was Tasmania, in 1997. Until that time, Tasmania had what had been deemed to be the harshest penalties for homosexuality in the western world, and had some attitudes towards homosexuality that had very much attracted world wide human rights attention. In 2017, twenty years after Tasmania declared that they would no longer consider homosexuality “wrong” in the eyes of the law, the Australian people voted for same sex marriage. The debate on social media and amongst our politicians was, in my opinion, massive. Everyone fought for their “truth”. These truths were based on opinions, so the reality that we were all living about homosexuality was a reality that was based on the majority of us treating our opinions as fact. Those who agreed with same sex marriage fought hard for their truth, whilst those who opposed same sex marriage fought hard for their truth. For twenty years, Australian states had no longer held their opinions of homosexuality as a legal truth, potentially providing a path for homosexuals to feel legitimised as people. Yet, the debate around homosexuality and, subsequently, same sex marriage was continuing. In 2019, two years after we voted to embrace same sex marriage as a country, the media declares a photo of two males (who they misinterpreted as being in love) as a “coming out”.

Homosexuality has been legal for at least 20 years in Australia, and homosexuals are now legally able to marry. So why would the media interpret the (apparent, in this case) announcement of a gay relationship as a big thing?

My interpretation is that, although society’s approach to homosexuality is changing, our ways of being are not changing fast enough to accommodate that change. Up until twenty years ago, society lived the assessment that homosexuality was “wrong” as a truth, evidenced by our laws at the time. This learning that homosexuality was “wrong” was embedded in our society, and so formed part of our way of being, both as a society and as individuals within a society. Twenty years later, I think that we are generally more accepting of homosexuality within our society. However, it is possible that we have not removed that initial learning from our way of being, and so the actions that then become most available to us are actions that contain hidden judgements around homosexuality that, as a society, we probably don’t even realise we hold. In my opinion, one of the actions coming from that hidden judgement is to make a photo of two male people supposedly in love newsworthy and declare that their relationship needs a “coming out”. What if we shifted our societal way of being to remove that apparent hidden judgement? Would a photo of two people of the same gender who are in love then simply become a photo of two people in love?

This, I think, leads on to learning. What is learning? In my assessment, understanding what we mean by learning also requires an understanding of what we mean by “knowledge”. I once read what I think is a fabulous passage about knowledge in the book “From Knowledge to Wisdom: Essays on the Crisis in Contemporary Learning” by Julio Olalla. It is something that really resonated with me, and I would like to share it here:

“Knowledge has become another possession and therefore it has also become the object of greed. Wisdom, on the contrary, cannot be a possession. It cannot be traded, regulated, or registered. It cannot be owned by any individual, because it lives in a territory that is not solely human, it is shared with the gods. Wisdom is not what we know about the world, it is what the world discloses for us. If knowledge can live in greed, wisdom can only live in gratitude. If knowledge belongs to thought, wisdom belongs to soul. If knowledge creates silos and divisions, wisdom integrates. If knowledge is knowing about it, wisdom is being it.”

My interpretation of this is that, traditionally in the western world, we tend to look at knowledge as something to be “had”. We see knowledge as a way of gaining power and control. This is evidenced by our school systems, where our children are generally placed in classrooms and taught knowledge. Throughout their school life, they continue to be judged on how successful (someone else thinks) they have been in obtaining that knowledge. I hold an assessment that interpreting knowledge in this way opens us up to interpreting our learning in terms of how quickly we can acquire knowledge. This, in turn, then encourages us to develop assessments around learning that, although perhaps supporting us in our focus on acquiring knowledge, may not be useful in helping us to adjust to a constantly changing life. For example, if we declare that we are still a learner with regard to a specific topic, this tends to lead to the assessment we have not successfully gained enough knowledge; we are not yet good enough. If someone is a learner with regard to a specific topic, then the assumption is that they don’t “know” that topic.

So, what if we were to think of knowledge as the ability to take action, rather than a physical “thing” to be had? My interpretation is that this really shifts the focus of knowledge, from a grasp for power to a willingness to look out for what best serves ourselves and others, and I would like to provide an example to explain what I mean.

When I walked into my very first coaching conversation all those years ago, it could be argued that I simply didn’t know what to do in a work environment that seemed to be creating uncertainty for me. It wasn’t that I didn’t have the knowledge to do my job; I had the relevant academic knowledge and thinking that would generally have supported me in my job. However, in an environment where it was considered acceptable to bully people, where everything seemed so uncertain, and where my self-doubt was being triggered at a rate of knots, I didn’t know what actions to take. I didn’t know how to respond to interactions where people were screaming and swearing at me in a full meeting room whilst thumping their fists on desks. I didn’t know how to respond to requests that I assess to, at best, be requests with no consideration for the understanding and context that my team and I could add to the situation and, at worst, blatant bullying orders that perturbed people such as myself enough that the only option available seemed to be to give up. I simply did not know how to take action appropriate to these circumstances. This does not mean that I was incompetent in gaining knowledge. It simply means that the learning that I’d had until that point in time had not equipped me with the ability to take action in those circumstances. By owning that and declaring myself a learner, I was able to find new ways of taking action. Those new ways of taking action could then assist me in serving both myself and others, because the focus had shifted from one where I hadn’t learned “enough”, to one where I simply hadn’t learned what was going to be useful in that situation. And, thinking about it, why would I have learned it, if I had never encountered that situation previously?

We are not actively taught how to take action in life; our focus tends to be on gaining knowledge as a thing to be had. We tend to learn how to take action based on our culture, upbringing, society’s views at the time, and our own experiences. We progress through life and apply our learning as we go. This is interesting, because it means that we are learning from our past and applying that learning to our present to create our future.

Let’s think about this for a second.

What if, in the past, I had learned that the world was flat? And what if, by some quirk of fate, I had never received the memo advising that the world was no longer thought to be flat? I could potentially set off on a journey where I assumed that the world was flat. All of my decisions would be based on that obsolete knowledge. I might limit how far I travel because I don’t want to fall off the end of the earth. And, when I encountered a world that wasn’t flat, I might not know what to do because I haven’t had any learning about a world that isn’t flat. So, in effect, I have just created a whole future based on my obsolete past learning that the world is flat. This, I think, is how we tend to operate with regard to our interactions in life. It is important to note that no one is at fault here. We have learned what we have learned; we can’t apply what we haven’t learned. However, because we are looking at knowledge as a thing to be had, rather than a possibility for taking action, I don’t think that we see relearning what we have learned as something that would be useful; our learning about knowledge leads us to thinking that we “got it wrong”. And so we continue to take learning from the past, and apply it to our present interactions without realising that the learning might already be obsolete, to create our future.

When we interpret knowledge as an ability to take action, I think this opens us up to also seeing learning as being an opportunity to provide us with greater possibility.

How, then, does this relate back to our constantly changing world?

My interpretation is that, as we deal with our constantly changing world, we can fall into situations were, through no fault of our own, we are applying obsolete learning and therefore operating from old ways of being. This learning may then not serve us in dealing with the changes that are occurring throughout our existence, and our existence then potentially becomes one of suffering.

What if we approach this change as a learner, aiming to learn how to increase our ability to take action?

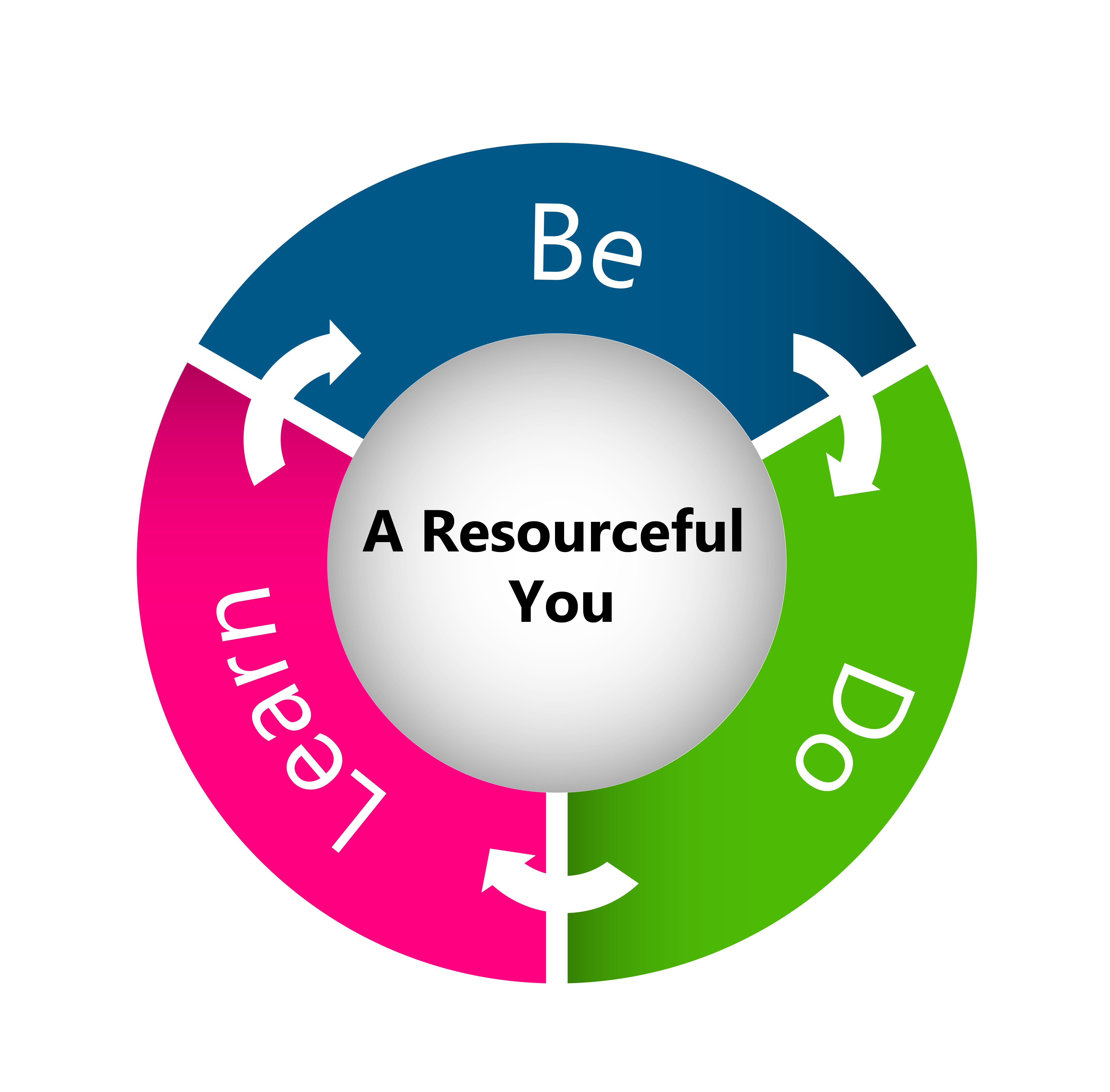

In earlier posts, I have mentioned that our way of being determines the actions that we take. Not every action is available to us from every way of being. In the natural course of every day life, we “be”, and then we “do”. What we do is based on how we are being. Life becomes a cycle of being and then doing. Be. Do. Be. Do. Repeat. What if we were to become a learner and try to learn from how we are being and its impact on what we are doing? And what if we then applied that learning to how we are being, so that we can bring about different ways of doing? My interpretation of this is that if we continue to be a learner, observe our way of being, and then apply that learning to our way of being in order to shift what we are doing, we become more resourceful in dealing with the constant change that is very much a part of our lives. My pictorial interpretation of this approach is below:

Something to remember is that human interactions will involve more than just ourselves. When other people become involved in interactions, then we have more than one way of being to consider. In this case, I think it is important to remember that we can only change our own way of being. In doing that, it might be that other people respond differently and change their way of being. However, only they can make changes to their way of being, just as only we can make changes to our way of being. What we can do, however, is to try and be aware of how others may be interpreting the world – the things that are important to them, their moods, their assessments of the world, etc, and then interact to them in a way that speaks to those interpretations.

By being aware that old ways of being may not always serve us, and by continually being a learner, looking at what might be happening for us in our language, emotional spaces and body, we can shift our way of being to one that is more useful for us. The result, I think, is a more resourceful version of ourselves that has access to the possibility of managing the constant change that is occurring in our lives and within society today.

Note: This post came about as a result of a question posted by Scott on the An Ontological Life Facebook Page in response to a Talkback Tuesday blog post. Thank you, Scott, for requesting a discussion on “Change as a constant state of life”, and for the inspiration that this request provided.

Acknowledgements:

– The featured image in this blog post is a photo by Pixabay on Pexels

Who am I?

I am a leadership and life coach, available for coaching and facilitation services. If you feel that it would be useful to have a conversation with me, please feel free to view my services on the Leading and Being website.

Awesome article. Well done.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

I should share with you the situation in Uganda just for the last 15 years

LikeLike